Maciej Jakubowiak discovered Ulysses when he was working on his dissertation. He moved all his writing into the app and eventually realized that it is the only tool he needs. In this post, the Polish book author and essayist reflects the findings on the way to his current writing process.

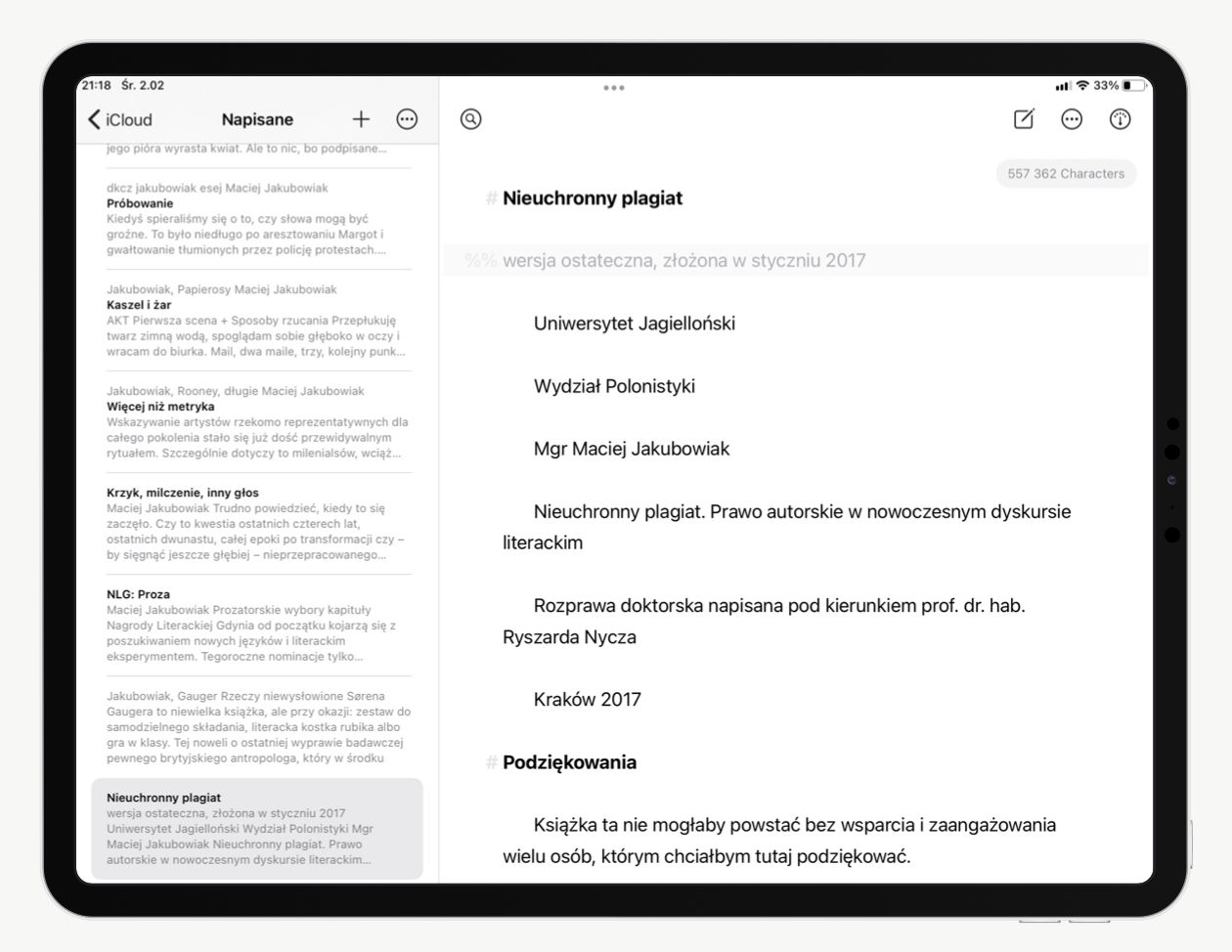

I published my PhD thesis titled “Nieuchronny plagiat. Prawo autorskie w nowoczesnym dyskursie literackim” (Inevitable plagiarism. Copyright law in modern literary discourse) in 2017. In one chapter, I refer to the American literary scholar John Livingstone Lowes’ analysis of the work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an English romantic poet. Trying to explain how Coleridge’s imagination worked, how it absorbed and transformed works of other writers, Lowes creates the figure of the well. The well is a metaphorical space, buried deep in one’s mind (one could say it’s similar to what Sigmund Freud called the unconscious), where every word ever read or heard, every picture ever seen, every experience and emotion, where all of this, kept chaotically together, mixes and transforms, producing unprecedented shapes. From time to time, the writer can reach into the well and bring something artistically or intellectually unique out into the light of day. In my case, the well has its name: Ulysses.

I discovered Ulysses when I was working on my dissertation. I moved all my writing into the app, and eventually, I have realised that it is almost the only tool I need to write. But along the way, I tested a lot of software. Testing and discovering new software is a perfect way of procrastinating, and procrastination, although it may get bad press, is an important phase of a creative work. Here’s the story of my discoveries.

Feeding the Well

Writing a PhD thesis — actually every kind of writing — starts with reading. In the case of literary studies, it means reading tons of books and articles. And making notes. Reading without making notes is like watching movies without popcorn, no fun. Notes are a way of participating in a text; they are an active involvement in a process, which a written text is only a part of. That is true for every kind of reading, but in the case of academic work, it is a fundamental thing.

Because of that, a long time ago, I moved all my reading (and eventually my writing) to iPad. Before that, I had tried Kindle, but it’s not so great for dealing with PDFs (and a lot of academic writing is available in the form of PDF files), and it feels slow. For some people reading on a tablet seems difficult, mostly in the night when a bright screen light may, quite literally, hurt eyes. Fortunately, every PDF reader I have used has had a night or dark mode, which inverts colours and allows you to read white on black. Together with “night shift”, implemented in iOS some time ago, it creates an almost perfect reading experience. Or maybe my eyes and brain just got accustomed.

Reading without making notes is like watching movies without popcorn, no fun.

I tested a lot of PDF and ebook apps, but eventually, I found my good-enough set of tools. I read PDFs in PDF Viewer, which is simple, fast and efficient. It uses iOS’ native file management system and has a dark mode. To read ebooks, that is, epub files, I use Apple Books — there’s nothing better in this field.

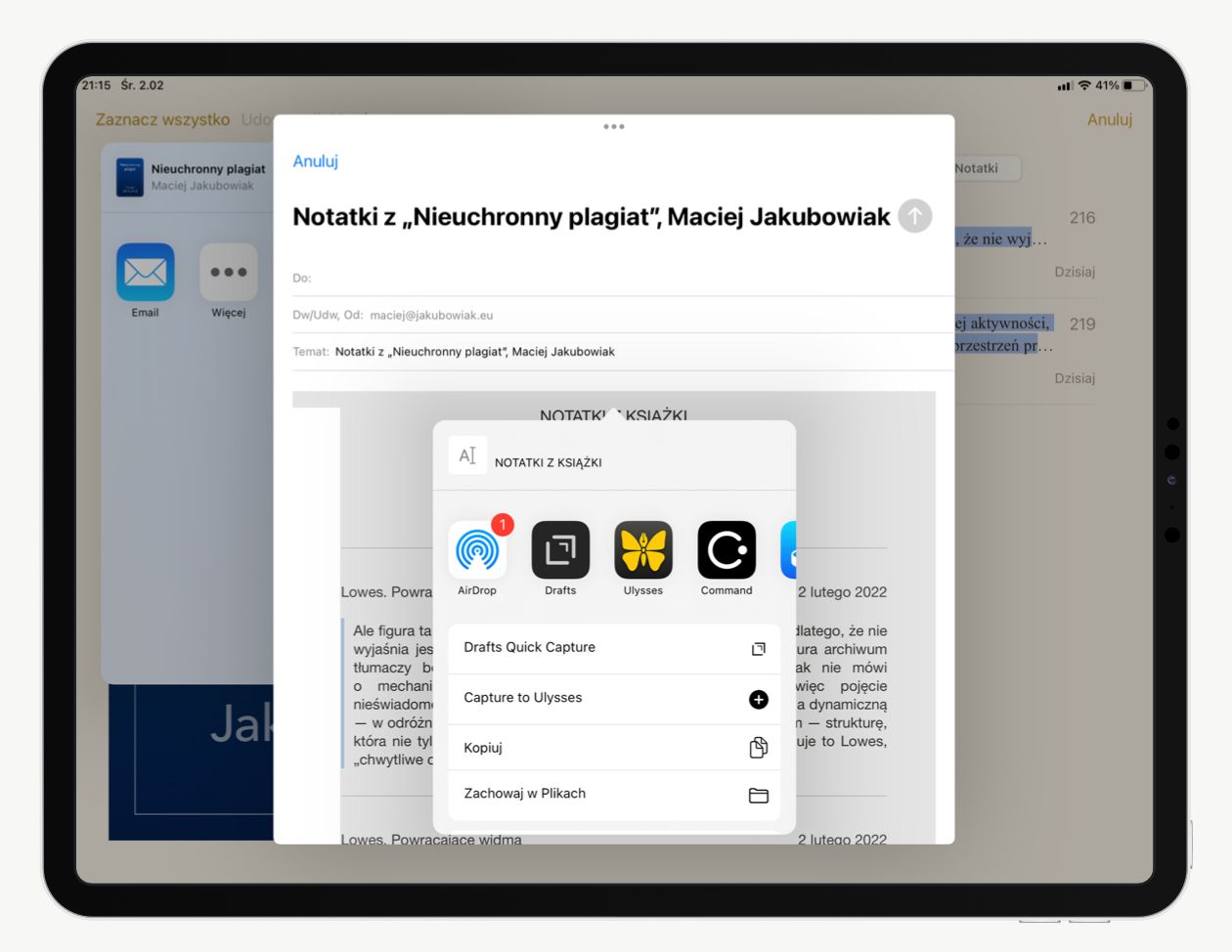

When I read, I highlight extensively and make notes, to remember why a quote is important or quickly note an idea that came to my mind when reading a given fragment. After I’m done with a book or an article, I export all highlights and notes to a markdown file. That part may be tricky. To export notes from a PDF file, I use a separate app called Highlights. And to export notes from Apple Books, I use this workaround: I tap on the hamburger/outline icon, then on the Notes section, then on the share icon, choose “Edit Notes” → “Select All” → “Share” → “Mail”, then select all text, choose “Share” from a pop-up menu and only then save it to a selected app (see, Apple made it difficult, but not impossible).

I could save it directly to Ulysses, but I use an intermediate app: Drafts. I use it to clean up the notes a bit, get rid of unnecessary elements and so on (I use a self-made Drafts macro). By the way, Drafts is also a great app to quickly jot down ideas that come to my mind at any part of the day. I don’t need to wonder where they should go; I just put them into Drafts, which I treat as an Inbox for thoughts.

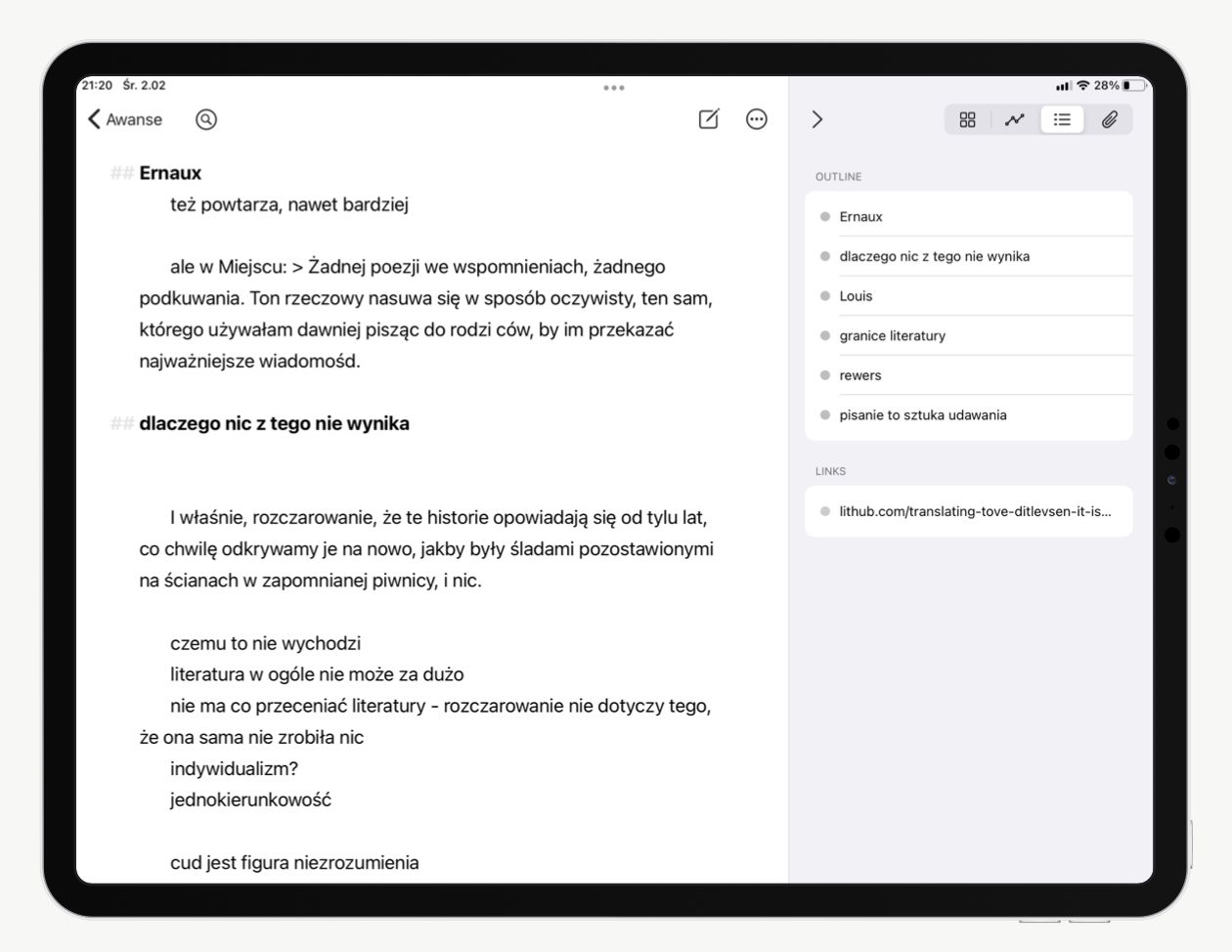

Finally, I move my notes to Ulysses. For each project, be it an article or a book, I create a separate group. This is my well. At first, I don’t care about any specific organisation; I just try to gather as many notes as possible and let them live there for a while. From time to time, I may go through them to make sense of what I already have and where I should look for more material. But the well needs some time on its own.

Organising

When I get a feeling that the well is full enough (and sometimes you just know), there comes time to organise all of it. I am aware there are a lot of apps that promise to organise notes on their own, or at least to provide their users with sophisticated tools to do it. I know there’s a hype for Obsidian; I am aware there are apps like Craft, Notion etc. I’ve really been there; in my whole career, I have tested a lot of similar apps, like Evernote, Simplenote, and countless others. At some point, I even created complicated workflows in Editorial.

I realise some people may find these tools useful. But here’s my discovery: what you really need is to be intimate with your notes. To take care of them, to visit them once in a while, to explore your observations from the past and feed them to the best app for organising notes and ideas: your own brain.

For everything else, Ulysses has enough tools: keywords, smart folders, quick search also known as command-O (⌘O). If you really need to find something or organise big sets of notes, these tools should be enough.

Outlining

However, for a long time, I have believed there is one thing that Ulysses could not do, which is transforming notes into a structured plan. And that is a necessary phase: a heavy mass of highlights, notes, and ideas must be transformed into an organised form. Some people believe they can organise their material in their heads or that they will find the appropriate notes when they write. They are wrong. I work as an editor, and I can easily tell when someone had a plan and when someone didn’t, and the second option is always worse. It leads to chaotic arguments and repetitive narratives. Trust me: you need a plan.

So, for a long time, I have believed the plan needs to be strict. And Ulysses could not be enough, so I used tools specifically created to be strict: mindmaps and outliners. I have done my fair amount of testing in this field as well and eventually have found great apps for the job: iThoughts for mind-mapping and OmniOutliner for, well, outlining. The former is great for creating the first big picture of a structure, and the latter is for seeing this structure in a linear way that can be translated into text. I did that with my PhD thesis, and I did that with my last book of essays: I went through all my notes, sheet by sheet, paragraph by paragraph, and I meticulously found a place for them in a huge structure.

But eventually (and it may have something to do with the fact that recently, after many years, I quit my academic career and decided to focus on literary writing), I realised I could create a plan in Ulysses. Again, it provides all necessary tools: six levels of headers, outline navigation, even keyboard shortcuts to quickly move paragraphs around. Maybe it is not so strict and hierarchical as a dedicated outlining app, but some level of disorganisation may not be so bad after all.

Writing

Keeping everything in Ulysses has this benefit: it is the app where writing will happen. And it may be beneficial to train your brain into an association that this is the place where all the creative work happens.

It doesn’t require long elaborations: Ulysses is a great app to just write. It has a clean interface and an even cleaner fullscreen mode. But contrary to popular imagination, writing is not a struggle between a writer’s mind and an empty page. Writing a PhD thesis is not this kind of struggle at all. Text is a living organism, feeding on ideas and notes coming from other places, constantly transforming and evolving. The great thing about Ulysses is that it understands (that is, its designers and developers understand) what this process looks like. There is a side panel where you can put attachments and notes. There are different ways to leave comments in the text. There are ways to split and merge bigger chunks that still need to find their proper place. If I insist that you need a plan, that is also because this plan will eventually be shattered in the process of writing

Ulysses is the place where all the creative work happens.

Anyway, writing a PhD thesis is a constant jumping back and forth between an outline, notes and the text itself. On iPad, it usually requires at least two apps (or two instances of the same app) in Split View and sometimes an additional one in Side View. It may be tough, it may be arduous, but there is nothing more motivating than a growing number of characters in the top-right corner of the app.

And there is nothing more demotivating than footnotes. I know there are people who like them, but I’m not one of them. Footnotes may be the main reason why I quit my academic career. I hate them. They’re boring; they require huge amounts of energy; they are ugly. For some weird reason, they are presented in multiple specialised formats and they are difficult to use, but there is no academic writing without footnotes. You need to have your footnotes right; that’s the basics. Coincidentally, footnotes may be the main reason why academics may avoid writing on iPad: there are many useful apps that help to deal with them on macOS (like Papers, Zotero, Mendeley), but they aren’t really helpful on iPad (at least they weren’t when I was finishing my thesis in late 2016).

However, I found a way to deal with these beasts: Pandoc. I used a combination of the Pandoc markdown processor, which easily converts markdown files into docx (and many other formats), and a BibTeX library. I had all my references stored in a Bibtex library (a structured text file that can be managed with many free apps), each item with its own unique identifier. Whenever I needed to make a footnote to a specific item, I simply put this identifier in the text, in the form of [@SomeTitle2016]. When the text was ready, I exported it from Ulysses as a markdown file. Then I needed, unfortunately, to open an old Mac, for the sole purpose of running a simple Pandoc command which produced a well-looking docx file with all footnotes in their right place. I know it sounds complicated and technical, but haven’t I mentioned that footnotes are terrible? They are.

But that is also how the final text of my PhD thesis was made. After many years, after megatons of books read and tons of notes produced, after hundreds of hours of writing and editing, after all splits and merges, one day, I was ready to make the final merge. I joined all the chapters, exported a markdown file, ran it through Pandoc, and made some final polish. And there it was: my PhD thesis. A thing previously unimaginable, somehow miraculously extracted from the well.

The End?

That could be a nice end to this story, but, of course, that’s not the end of the story. There were some additional edits and comments from my colleagues and friends. All of it happened in the docx file. And eventually, I exported the file to a PDF and then printed it, and only then it was ready and final. Well, not really, because later the thesis became a book, so it needed even more edits. But at some point, when the file’s name looked like “Thesis-final-v.5.6-really-final-new-edits-shipped-now-really-final-oh-my-gosh-when-it-will-ever-end-DONE-not-yet.docx”, I was able (and that is another cool thing about this app) to import it back to Ulysses. Now the thesis itself is a part of the well.