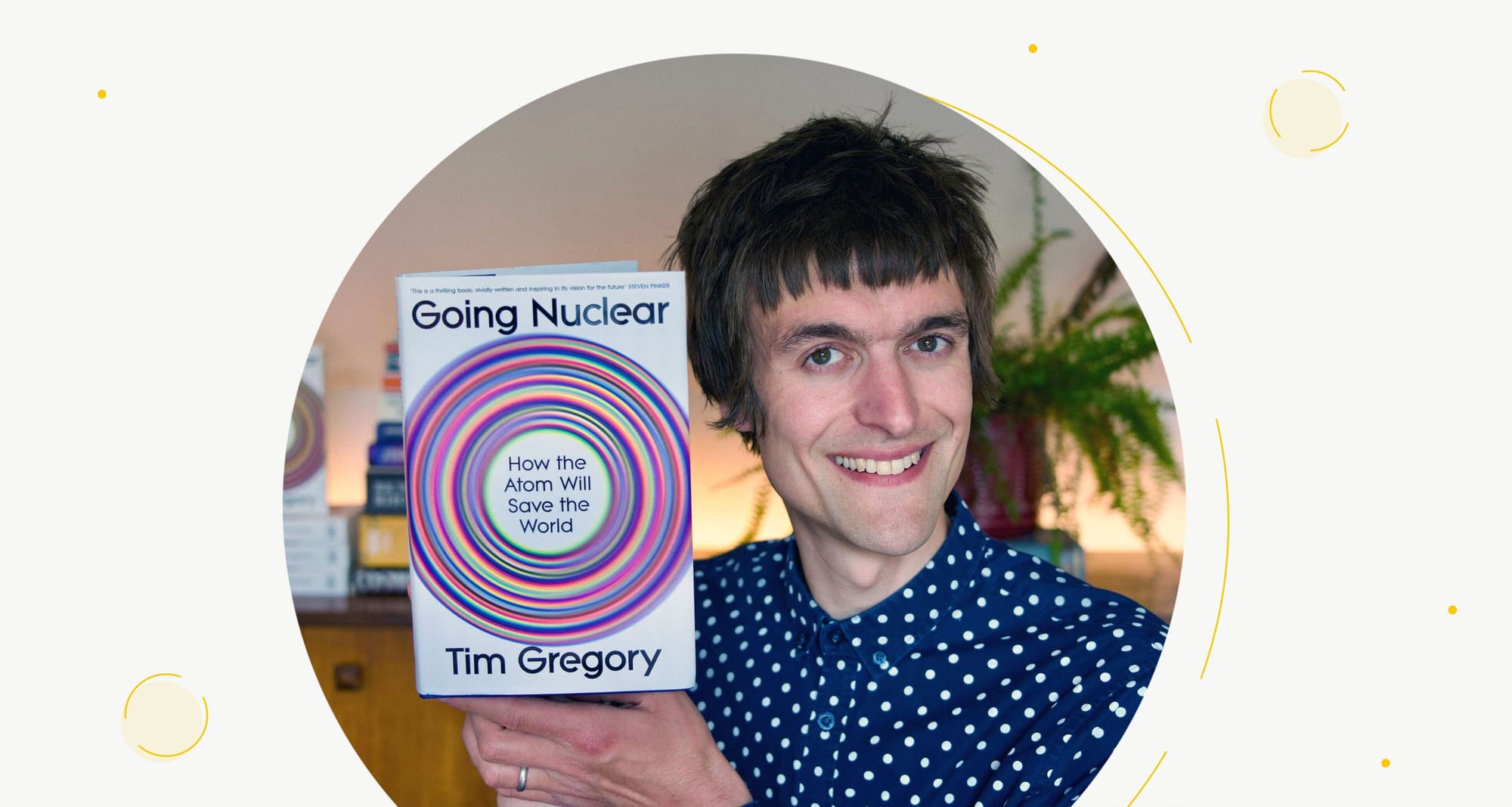

Dr Tim Gregory is a nuclear chemist at the United Kingdom National Nuclear Laboratory at Sellafield, a public speaker, broadcaster and author of Meteorite: How Stones from Outer Space Made our World. In 2017, he was a finalist in BBC2's Astronauts: Do You Have What it Takes and has also presented on BBC's The Sky at Night and Channel 4’s Steph’s Packed Lunch. He has a PhD from the University of Bristol and lives in the north of England. His website is www.tim-gregory.co.uk.

What initially sparked your interest in nuclear science, and how did that passion evolve over time?

I’ve loved science since I was a kid. When I was 17, I did a physics project at school titled ‘How does nuclear power work? And will it save us?’, and so my interest in nuclear science has always been there.

Funnily, I never set out to be a nuclear chemist for my day job. I fell into it after a sideways career change from academic research. It turns out the skills I picked up during my PhD in meteorite science—mass spectrometry, analytical chemistry, element separation, radioactive decay mathematics—lend themselves perfectly to being a nuclear chemist.

Was there a defining moment that led you to writing and science communication?

It was a series of small steps rather than a defining moment.

As a student, I volunteered at my local museum and started giving talks in local schools. From there I developed a knack for talking to people, and it’s become more and more a part of my life since then.

As for writing, I’m inspired by many of the great authors I’ve read, especially Carl Sagan, Steven Pinker, and Richard Feynman.

![Tim’s cat \[cat’s name], demanding attention while he is writing his book.](https://stories.ulysses.app/content/images/2025/05/tim-gregory-desk.png)

Going Nuclear is your second book. Your first one, Meteorite, explored the formation of the Solar System, while this one delves into your own field of nuclear science. What inspired you to write about your profession?

One of the best things about science is that we can use it to make the world a better place and reduce the amount of unnecessary suffering. Nuclear science encapsulates this perfectly, which is why I wrote Going Nuclear.

I show how nuclear science can give us energy abundance, help us protect the environment, let us cure cancer in new ways, allow us to create new types of super-crops, and—one day soon—let us thrive on the surface of other planets. It’s a far-reaching and fascinating subject.

The book challenges common narratives around climate change and nuclear energy. What are some prevalent misconceptions about these that you aim to clarify?

I tackle them all head-on! There’s a lot of myth-busting in this book.

There’s a perception nuclear is unsafe; yet the data show it’s the safest way to generate power. There’s a perception it’s expensive; yet the data show that when it’s done properly, it’s the cheapest way to make electricity. There’s a perception it’s dirty; yet the data show it’s the cleanest form of energy production with the lightest burden on the ecosystem. There’s a perception nuclear waste is unsolvable; yet Finland—which has a grid that’s one-third nuclear—has implemented a working geological storage solution.

It was fun picking off the misconceptions one by one as I wrote.

Both Meteorites and Going Nuclear tackle complicated scientific topics, but you intend them to the general public. How do you approach structuring and presenting such complex information effectively?

I have three main tools I use to get around this problem.

- I try remembering what it was like before I knew all this stuff and write for that person. Assuming too much knowledge is a sure way to lose your audience.

- I avoid technical and corporate jargon. It kills the prose.

- Tell stories when possible. There’s a time and a place for stating facts clinically, but most of the time it’s best to weave those facts into a narrative.

Nuclear energy could be a polarizing topic. Have you faced any unexpected challenges or resistance while researching or talking with experts?

No, quite the opposite. I think the anti-nuclear gut reaction that once dominated the conversation about nuclear power is waning. Everybody wants a cleaner world and cheaper energy bills—people are starting to talk about nuclear again, and so Going Nuclear is coming out at a great time.

What do you think is the biggest barrier to public acceptance of nuclear energy, and how can scientists and communicators help bridge that gap?

People tend to be suspicious of things they don’t know a lot about. Part of my motivation in writing this book was setting the record straight, and then at least people can make an informed decision about nuclear power.

Many people associate nuclear power with accidents like Chernobyl and Fukushima. How do you address these concerns in Going Nuclear?

There’s a whole chapter on Chernobyl and Fukushima in Going Nuclear. I don’t shy away from anything, and I set these accidents in their proper context. For example, even when you consider the consequences of Chernobyl and Fukushima, nuclear is as safe—megawatt-hour for megawatt-hour—as wind and solar power; it’s orders of magnitude safer than fossil fuels.

What was the most surprising or counterintuitive fact you discovered while writing this book?

One of the most surprising things I discovered was all the imaginative uses for radiation. For example, it can be used to breed new types of drought-resistant crops; it can be used to eradicate pests and save harvests; and it’s even being used in the fight to save the rhino from poachers.

There’s a whole chapter on the novel uses of radiation, and it was one of the most fun to write.

This is your second book written in Ulysses. How has your use of Ulysses evolved while working on Going Nuclear?

The addition of the ‘Projects’ was awesome. I keep my manuscript separate from all the other bits and bobs I’m working on, and it makes the workspace feel cleaner.

I also relied heavily on annotations. They saved my life! I added notes, explanations, screenshots, links, file paths, etc. into my manuscript for my own future reference. And then, when it came time to send my manuscript to my editor, I just excluded them from the export. It was a total game-changer for me working this way, and it means I can always find the exact source for a piece of information in less than a few seconds.

Beyond Ulysses, what other writing tools or software do you use in your workflow?

My main writing tool besides Ulysses is Zotero, which I use to store and manage all my sources. I’d be lost without it.

As a nuclear chemist, author, and public speaker, how do you manage these diverse roles, and how does writing fit into your daily routine?

It’s incredibly time-consuming. I’m either reading, writing, or working on a new talk every single day, and normally for a good chunk of at least one day on a weekend.

Having said that, I stopped using social media some years ago, and it’s surprising how much time you really have in a day if you’re disciplined and minimise distractions. My biggest tip for budding writers is put down your phone and reclaim your time!

Do you have any guiding principles or philosophies on writing in general and writing as a scientific communicator?

My highest ideal is writing truthfully and clearly. Everything else—style, humour, personality—is desirable but optional.

Are there any upcoming projects or topics you're eager to explore in your future writing?

I recently started writing articles on Substack on topics that interest me, ranging from space exploration to energy to general science. I do all the writing in Ulysses. This will be my focus for the foreseeable future. Maybe one day I’ll be fortunate enough to write another book :-).

If you’d like to read more from Tim, make sure to check out his website or get a copy of his new book, Going Nuclear (UK Edition, US Edition).