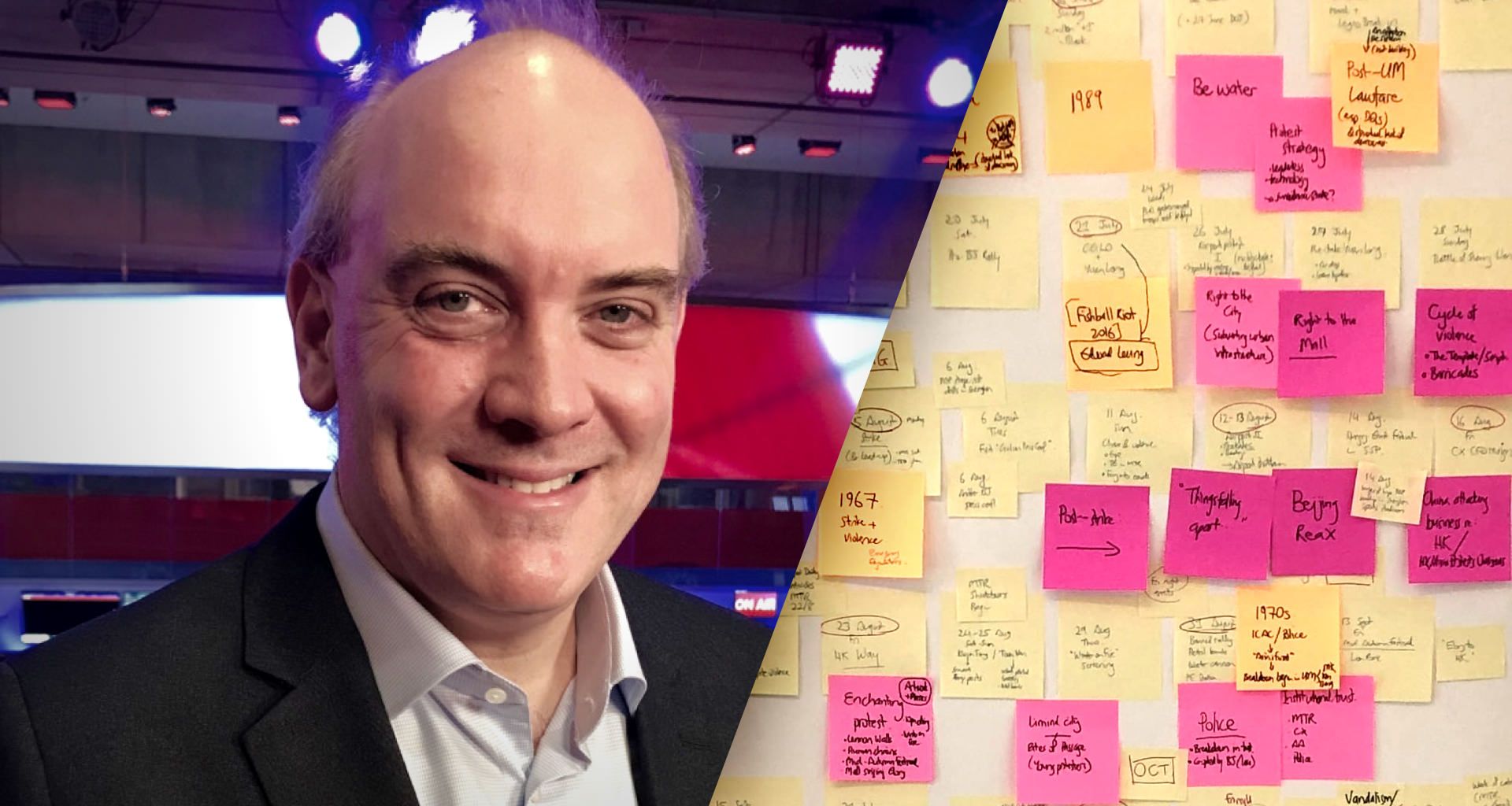

Antony Dapiran is an Australian writer who has been residing in Hong Kong for many years. In our interview, he talks about his attraction to Hong Kong, the gradual transition from lawyer to writer, and the process of writing his latest book about the protests in the city in 2019.

Please tell us something about yourself and your professional background.

I am a writer, photographer and lawyer based in Hong Kong. I spent twenty years practising as a corporate lawyer in international law firms, based in Hong Kong and Beijing. In recent years, I have increasingly focused on my writing, and have been an active freelance writer as well as publishing two books on Hong Kong politics and protest culture.

You’re a long-time resident of Hong Kong but were born in Australia. How did you get there, what attracted you to Hong Kong?

Hong Kong is such a dynamic place, a city that is “spectacular” in all senses of the word. The city captured my imagination when I first visited it on a family holiday as a child, and I always hoped to return. Later, I studied law and Chinese language at the University of Melbourne and also spent two years studying on exchange at Peking University. After graduation, I wanted to work somewhere that would enable me to use both my legal qualification and my Chinese language skills, and Hong Kong was the perfect place to do just that – as well as to fulfil a childhood dream.

Hong Kong is “spectacular” in all senses of the word.

How is the mood there right now, in the current situation? In the media, Hong Kong is presented as a role model for other states, thanks to low COVID–19 infection rates. Does that reflect in everyday life?

Hong Kong has indeed fared relatively well during the coronavirus outbreak. In part, this has been thanks to an early and rigorous programme of testing, contact tracing and quarantine. However, more importantly, the Hong Kong community has a very high awareness of these issues after our city suffered during the SARS outbreak of 2003: for example, face masks have been very common in Hong Kong since then. Thanks to all of this, life has been much less disrupted here than it has been elsewhere, although the community is remaining vigilant.

You’re not only a writer but also a lawyer. What role does writing play in your life? Do you have two professions, or do you write in your spare time?

I have been making a gradual transition from lawyer to writer over a number of years. I began writing in my spare time while still working full-time as a lawyer, during Hong Kong’s last major protest movement, the Umbrella Movement of 2014. After my first book came out in 2017, I began to devote more time to my writing, and since last year, as all of my time came to be consumed covering the ongoing protests and working on my latest book, I have taken a break from legal practice.

Earlier this year, you published a book about the anti-government protests in Hong Kong in 2019. Please tell us more about it.

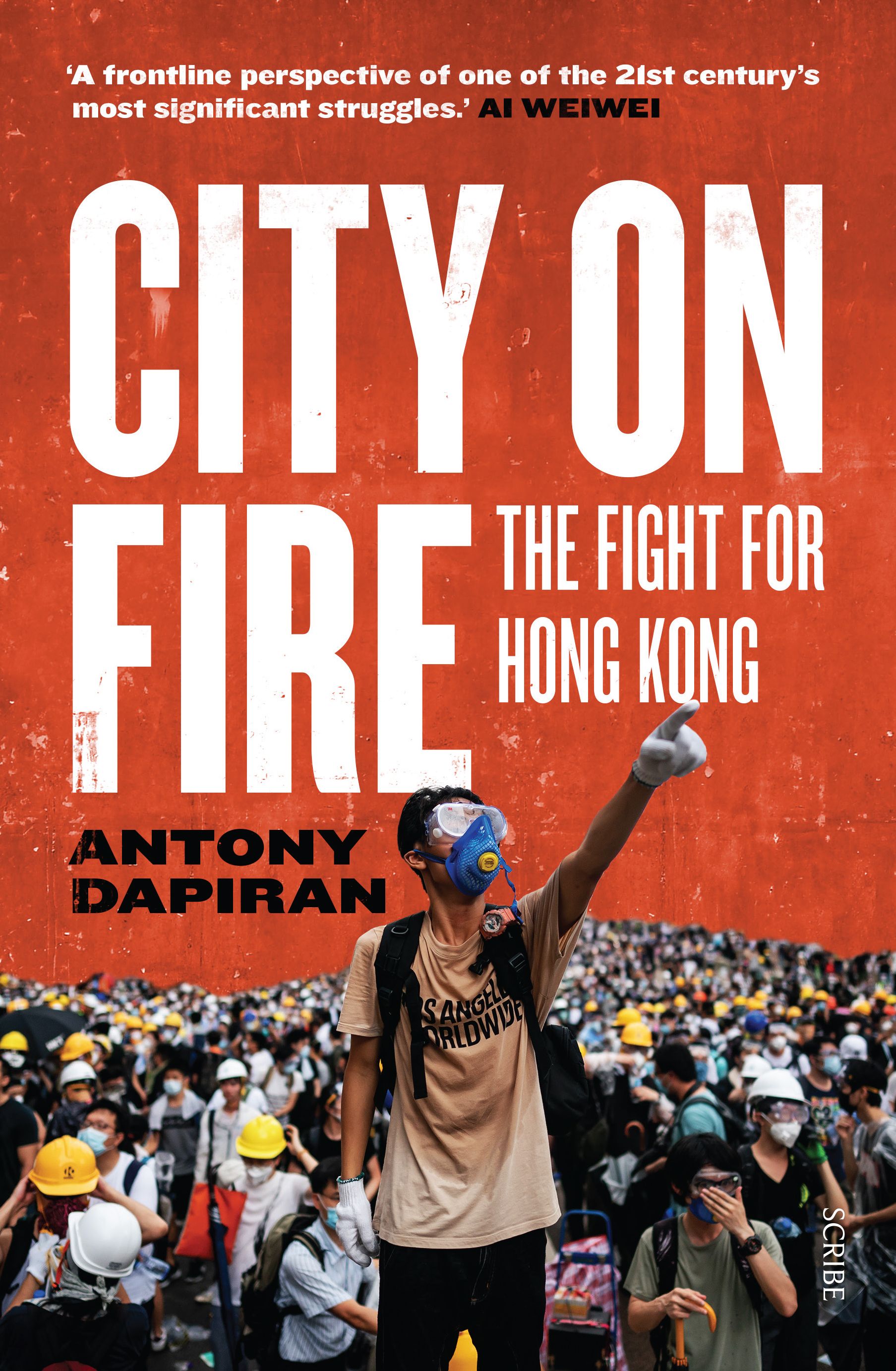

My new book, City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong (published by Scribe Publications) is the result of my on-the-ground reporting of the protests that consumed the city for seven months last year. In the book, I give a detailed account of the background to and course of the protest movement and situate it in the context of Hong Kong’s long history of political protest. I also examine the many cultural aspects of the movement and look at the implications of the protests not only for the relationship between China and Hong Kong but China and the world.

Please tell us about your book writing process and how you made use of Ulysses.

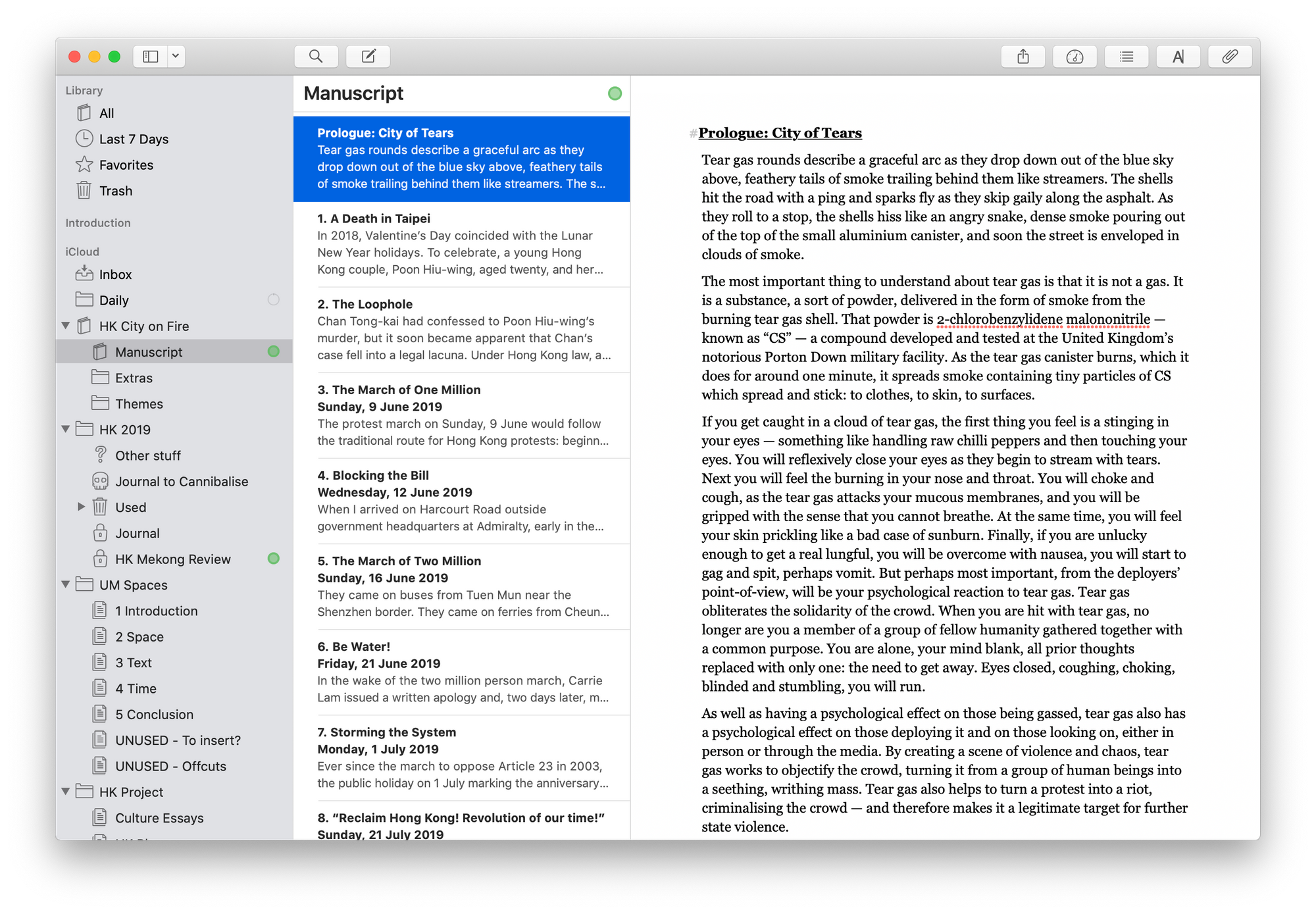

I wrote the entire book in Ulysses. The book was written within an extremely tight timeline: I contracted to write the book in September, with a deadline of Christmas to deliver the manuscript to my publisher, and a March target publication date. (It’s the kind of crazily ambitious publishing schedule that my publisher Henry Rosenbloom at Scribe seems to thrive on!) The biggest challenge I faced was pulling together a large and complex amount of material in this timeframe, and all while events on the streets were still unfolding. Ulysses was indispensable in helping me to do this.

From the beginning of the protests, I was fairly assiduous about keeping a journal: every day while out at protests I would take notes on my phone, and put them into Ulysses at the end of each day, with a new sheet for each day. Into these sheets, I also added further commentary and analysis, key events, and links to news items.

I wrote the entire book in Ulysses.

I was also fairly busy during the protests writing freelance articles: I dropped all of these into Ulysses as well, and they became further source material which I referred to, and in some cases reworked, while writing the book.

Finally, I had written a dissertation the previous year on the Umbrella Movement protests as part of an MA programme in literary and cultural studies at the University of Hong Kong. This had also been written entirely in Ulysses, so the dissertation, as well as all my notes, were in there as well. I adapted some of this material for the cultural analysis portions of the book.

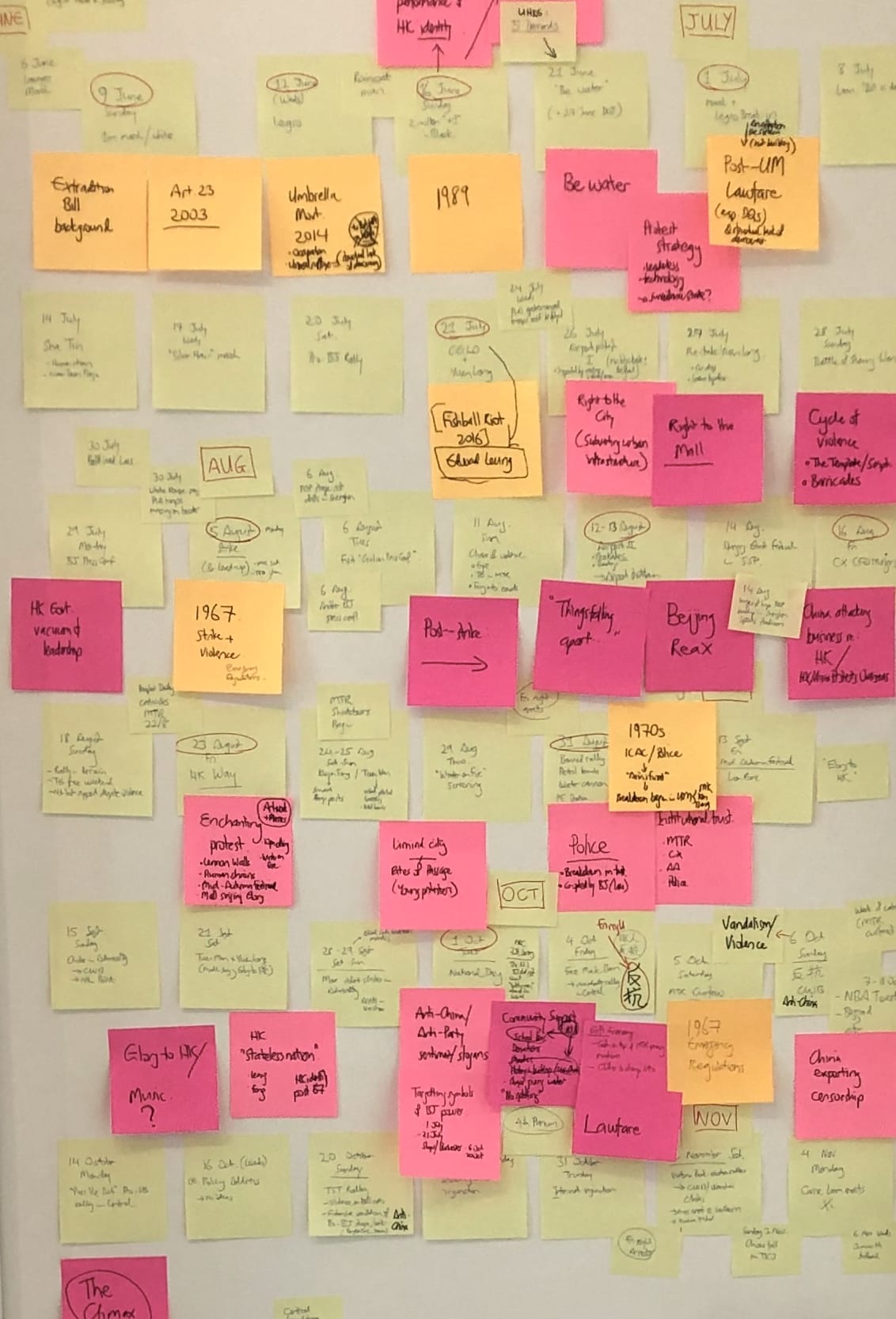

To figure out the structure of the book, I turned to a decidedly low-tech tool: Post-It notes. I took the three strands of my book – the events of 2019, historical events, and broader themes – assigned each a colour, and then wrote down all the elements I wished to include on Post-It notes and stuck them up on my study door until a structure emerged. (It was purely coincidental that this Post-It note plan resembled one of the protest movement’s famous “Lennon Walls”.) I am a very visual thinker, so having an overview of the whole book in a visual, physical form like this really helped me to figure it out.

With the structure settled, I set up a new group in Ulysses for the book manuscript, created a sheet for each chapter, and transcribed the Post It notes into the relevant sheets. Then, I got writing, using my journal entries as the skeleton and adding in additional material that I had there in Ulysses, as well as from additional research materials.

What do you like best about Ulysses? Do you have a favorite feature?

There are three key features that I love about Ulysses.

First is the file structure, using groups and sheets. It is impossible to write a book-length work in one single, continuously scrolling document (like, say, a Word document) and remain sane. Ulysses enables me to work with the book’s chapters as separate sheets, to see the entire book at a glance and to navigate quickly through the manuscript chapter-by-chapter. Restructuring the manuscript and shifting sections around then becomes very easy. But more than that, I would often break a single chapter into several sheets, enabling me to write a chapter in sections and then easily reorder those sections (or move them from one chapter to another) by moving the sheets around, before finally settling on the chapter draft and re-combining them.

It is impossible to write a book-length work in one single, continuously scrolling document and remain sane.

Second is the clean, uncluttered interface. It is distraction-free and elegant, in a way that no other competitors are. The app just gets out of the way and lets you write.

Finally, I am a firm believer in plain text and Markdown – partly as an extension of my general desire for simplicity, but also for the benefits of compatibility across platforms and future-proofing.

Using Ulysses was such a joy that I actually found it almost physically painful when I was finally forced to convert the manuscript into a Word document to go through the editing and revision process with my editor.

Which other tools and productivity apps are you using, and how do they help you?

For quick note-taking, I use Simplenote. (This was where I would jot notes while out on the streets covering protests.) I write articles and other short pieces – anything less than, say, 5,000 words – in Byword. Both of these apps, you will notice, share with Ulysses the virtues of a clean, uncluttered interface, use of plain text/Markdown, and sync across devices.

For archiving of online research materials, I use Evernote, although I must say I don’t love it. Evernote’s search function is not very helpful when trying to research across a large database, but, given that I do much of my online reading and capture on my phone (via Twitter or Instapaper), Evernote’s mobile app and sync functionality are much more robust than DEVONthink, which would be my preferred tool if they could get mobile and sync right. So I am stuck with Evernote for now.

Finally, I should mention Twitter and Substack.

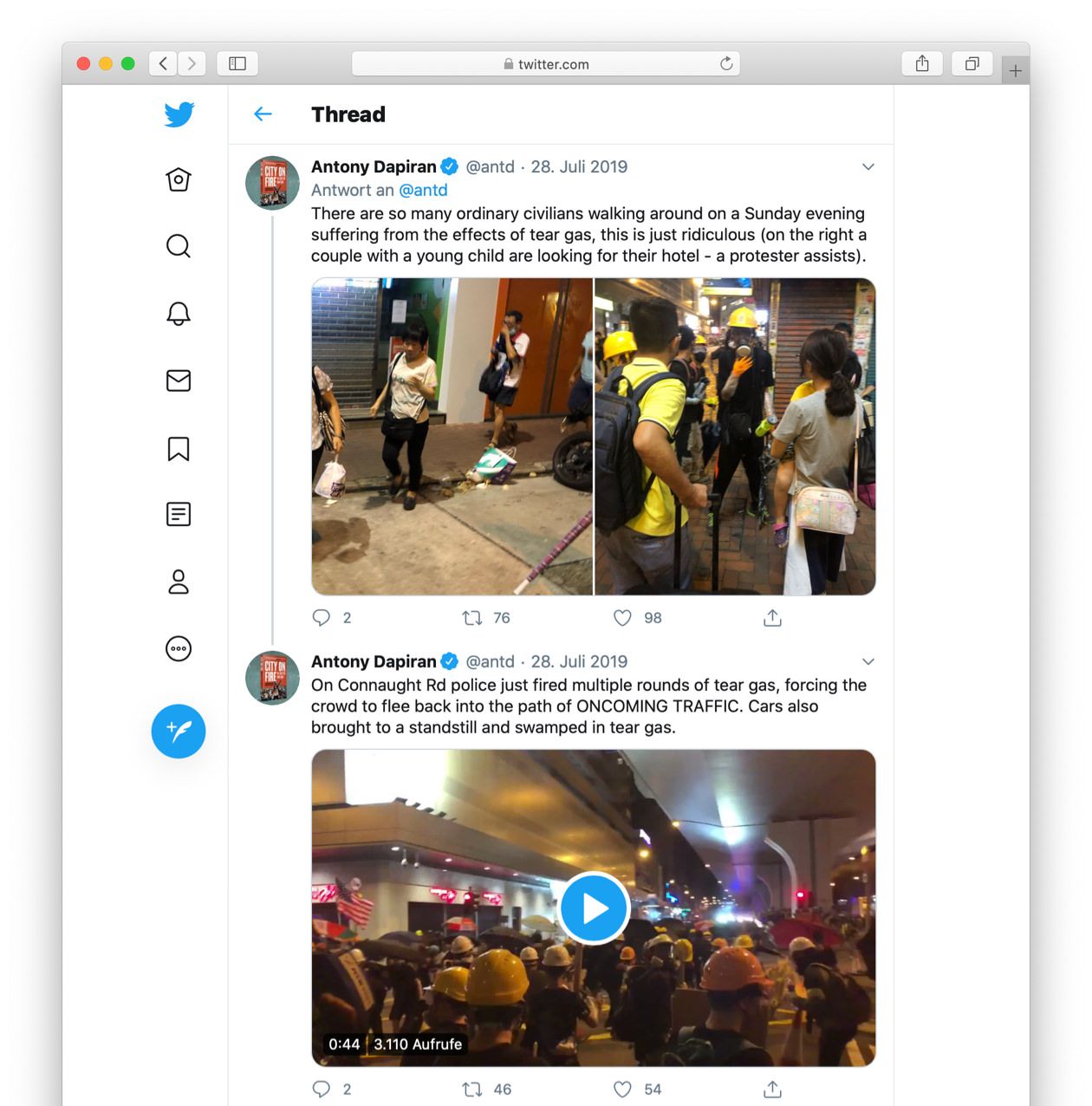

On-the-ground at protests, I used Twitter as a notebook and visual journal, posting photographs, videos and comments on events as they were happening.

This then provided a further source for writing the book: I could go back to my Twitter feed for a particular day to relive the events, which helped when it came to writing some of the more visceral descriptions of the protest experience. My Twitter threads also often become the jumping off points for longer written pieces.

I use my Substack newsletter for writing that is longer than a Tweet but less than a fully thought-out article. When I was writing the book, the newsletter was a place to workshop some initial draft material. Actually, I used it as a head-fake on myself: I am a dreadful procrastinator, so I told myself that I was writing the newsletter as a way to procrastinate writing the book, when in fact writing the newsletter was writing the book. That’s why my newsletter is called “A Procrastination”.

What else is essential to keep you productive? As an example, do you work in a particular environment or follow a timely routine?

To write, I need quiet – which in Hong Kong can sometimes be a challenge! I can’t write in cafes, or with music playing. If I can’t escape the noise, I play white noise through my headphones.

Other than that, to be productive, I really need an imminent deadline. I don’t think I would have written this book if it wasn’t for my publisher’s demanding deadline – and a tool like Ulysses to help me meet it!

To find out more about Antony’s work, visit his website or follow him on Twitter. Also, feel free to sign up for his Substack newsletter.